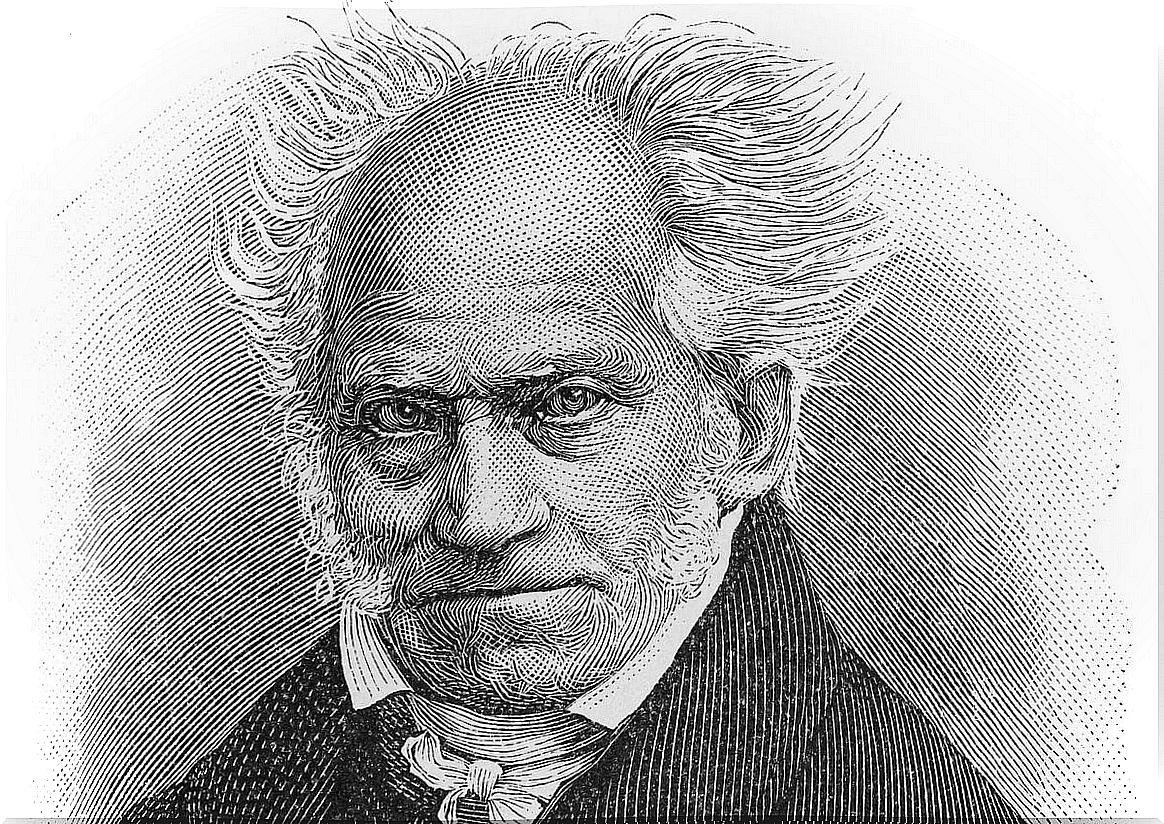

Deceptive Ways Of Arguing, According To Schopenhauer

Deceptive ways of arguing have been perceived and analyzed since ancient times. What makes them special is that they are capable of misleading our judgment in a superficial validity analysis; thus, we can get to use them or consider them valid without being aware that they hide a trap. However, scrutinizing them reveals that they are false.

Arthur Schopenhauer was one of the philosophers who took on the task of exploring these deceptive ways of arguing. This is the basic material of his work Dialectica erística or the art of being right, exposed in thirty-eight stratagems .

All the fallacies he cites are interesting and some are really funny. It tried to contribute formulas not to be defeated in an argument ; Here we quote them so that they do not deceive you again. Those we describe are some of the most prominent in Schopenhauer’s work.

Amplification

This mechanism is not about extending or expanding an idea, but about enhancing it. Thus, it does not matter if the idea in question deserves it; the point here is to set in motion one of the misleading ways of arguing.

To do this, the person who argues can use different resources, such as changing intonation or reformulating arguments so that one is worth two.

Homonymy

Homonymy is another deceptive way of arguing and consists of using a word that changes its meaning depending on the context, applying the appropriate meaning to consummate the deception.

For example: everyone who screams is a madman; the firefighter yelled at people during the fire; then the firefighter is a madman.

Generality and relativity

In this case, it is a matter of taking a statement stated in a relative way and applying it to a whole set or to all circumstances.

For example: there is a difference between “There are more and more corrupt in the administration of the legislative power” and “All members of the legislature are corrupt.”

Prosilogismos, one of the misleading ways of arguing

It is a chain of syllogisms where one may seem the logical consequence of the other, although it is not necessarily true.

For example: The brave are lucky; the cops are brave; therefore, the cops are lucky; Juan is a policeman; therefore, Juan is lucky.

False premises

When the statement from which something is concluded is not true. For example: All dictators are demagogues; Pedro is a demagogue; then Pedro is a dictator. This is one of the most common mistakes in political speech.

Petition of principle

It is a form of reasoning in which a statement already has implicit the conclusion that must be drawn from it.

For example: I always do the right thing; therefore, I never do something wrong; therefore, no one can accuse me of wrongdoing.

Circular question

It consists of inducing the other to agree with us through fallacious questions.

Irritate the adversary

As stated, it consists of adopting attitudes or expressing ideas with the sole purpose of annoying the adversary, so that he loses control and thus highlighting his own virtues, to the detriment of the “lack of control” of others.

Surely if we remember and go back to the last electoral debates, we will remember one candidate telling another not to be nervous.

Loosely concatenated questions

It has to do with confusing the other by asking questions in an unreasonable order. The goal is to create confusion.

This is the case of the film A very legal blonde / Legally blonde , in which an in-depth question is asked about an aesthetic procedure to conclude that the person questioned had indeed committed a crime.

Argues ad hominem

It takes place when an argument is called into question through the ruse of discrediting the proponent.

Thus, if A asserts B, but there is something questionable about A, then B is questionable. In this case, a logical assessment of the argument is not made, but a disqualification of the person issuing it.

Mutatio controversiae

It occurs when, in an argument, one of the interlocutors realizes that the other has made enough arguments to show that they are right. His adversary decides to suddenly change the subject to avoid agreeing with the other.

A typical example occurs when someone proves that another has acted improperly and he responds by accusing him of being unfair or too severe, or by victimizing himself.

Fallacia non causae ut causae

Also known as the “false cause fallacy.” It occurs when something that has happened immediately before is taken as the cause of something. It has two modalities:

- Non Causa Pro Causa. When a true cause and a false cause are mixed. For example: it has been a long time since I visited my mother. My mother fell ill and died. My mother died of sadness because I did not visit her.

- Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc. It is properly to employ a false cause, taking as this a newly produced event. For example: I saw a black bird in the middle of the street. Shortly after I was almost hit by a car. The black bird was the death that stalked me.

Exemplum in contrarium

It consists of opposing a particular case to invalidate a general conclusion, when the first does not have the validity to refute the second. For example, someone says that there is a disease that infects many people; another answers that he does not know anyone who has been infected, therefore the disease does not exist.

As you can see, all these deceptive ways of arguing are traps that anyone can easily fall into. They are also tricks that are easily laid. As an intellectual game they have some validity, but they are not worth using to satisfy a childish desire to be right.